The enduring beauty and structural resilience of brickwork are contingent upon meticulous maintenance, particularly the condition of the mortar joints that bind the structure. Over time, these joints, which are significantly softer and more porous than the bricks themselves, succumb to environmental factors—freeze-thaw cycles, wind-driven rain, and structural movement—leading to deterioration. The process of fixing wall bricks is fundamentally a restoration project, most often executed through a highly detailed technique called repointing or tuckpointing, supplemented by the replacement of spalled or cracked individual units. This comprehensive process ensures that the wall’s integrity is restored, its vulnerability to water penetration is eliminated, and its historical or intended aesthetic is preserved for future generations.

Phase I: Inspection, Diagnosis, and Safety Protocol

Before any physical work begins, a thorough inspection and diagnosis must be performed to understand the extent of the damage and, critically, its root cause. Surface-level repairs without addressing the underlying issue—such as poor drainage or inadequate flashing—will result in rapid failure of the new work.

Diagnosing the Deterioration

The diagnosis phase involves identifying several common failure modes:

- Mortar Deterioration: Joints appear sandy, cracked, or hollowed out. If a coin can easily scrape the mortar away, it is compromised. This is the primary trigger for tuckpointing.

- Spalled Bricks: Bricks exhibit surface flaking, peeling, or crumbling. This is typically caused by water penetrating the face of the brick and freezing, pushing layers off. These bricks must be replaced.

- Efflorescence: A white, powdery deposit on the brick face, indicating water soluble salts being drawn out of the wall structure as moisture evaporates. While aesthetic, it confirms chronic moisture intrusion.

- Cracking Patterns: Diagonal cracks, often stemming from corners or window openings, suggest structural settling or foundation movement, which requires consultation with an engineer before superficial repairs are undertaken.

Safety and Preparation

Masonry work generates significant dust and requires working at height. Essential safety gear includes safety glasses, dust masks or respirators (especially when grinding or chiseling), heavy-duty gloves, and secure scaffolding or ladders. The surrounding area must be protected with tarps or plastic sheeting to contain the dust and mortar splatter.

Phase II: Preparation and Mortar Removal (Raking Out)

The quality of the final repair is entirely dependent on the thoroughness of the preparation. The goal of this phase is to remove all deteriorated, loose, and compromised mortar without damaging the surrounding, sound brick units.

The Raking Process

Mortar is removed from the joints using one of two primary methods: manual or mechanical.

- Manual Removal (Chisel and Hammer): For historic or very soft brick, manual removal is preferred. A brick set chisel or a specialty joint raker is used to gently cut or scrape the old mortar to a uniform depth. This method minimizes vibration and damage to fragile brick edges.

- Mechanical Removal (Grinding): For hard brick and standard contemporary mortar, an angle grinder fitted with a diamond blade is used. This is faster but carries a higher risk of damaging the bricks. The blade must be slightly thinner than the joint width and carefully guided.

In both cases, the mortar must be removed to a depth of at least two to two-and-a-half times the width of the joint (typically 5/8 to 1 inch). This depth ensures that the new mortar has sufficient purchase and mass to bond effectively and withstand environmental pressures. Crucially, the back of the joint must be cut square, not V-shaped, to provide a proper shelf for the new material.

Cleaning the Joints

Once the old mortar is removed, the joints are cleaned of all debris and loose particles. This is achieved using stiff-bristle brushes, compressed air, or a vacuum. The joints must be impeccably clean. Before applying the new mortar, the raked-out joints and the surrounding brickwork must be thoroughly saturated with water. This essential step prevents the dry, porous bricks from rapidly drawing moisture out of the fresh mortar, which would otherwise result in a weak, crumbly joint that fails prematurely. The surface should be damp, but not dripping wet.

Phase III: Mortar Selection, Mixing, and Composition

The selection and mixing of the new mortar is perhaps the most technically critical part of the repair process. Using mortar that is too hard (high cement content) compared to the original, older mortar or the brick itself is known as ‘over-pointing’ and is detrimental. A joint that is harder than the brick will force any structural movement or moisture expansion to be absorbed by the softer brick, causing the brick face to spall (fail).

Mortar Type Matching

The standard industry practice is to use a softer mortar than the surrounding masonry. Mortars are categorized by their ratio of Cement (C), Lime (L), and Sand (S), leading to Types M, S, N, and K, listed from hardest to softest:

- Type N (Normal): The standard choice for most modern and general repointing above grade. It offers good durability and workability.

- Type S (Structural): Used for projects requiring higher compressive strength or below-grade work, but often too hard for historic repointing.

- Type K (Soft): Generally reserved for historic applications where the original mortar was extremely soft and lime-heavy.

For most repairs, a Type N or even a Type O (a slightly softer variant of N) mortar is appropriate. It is paramount to match the new mortar to the original in color, texture, and strength. The color is achieved by selecting the correct sand and, if necessary, adding mineral-based pigments.

The Mixing Process

Mortar should be mixed in small, manageable batches. The dry ingredients (cement, lime, sand, and pigment) are thoroughly blended first. Water is then added slowly until a cohesive, workable consistency is achieved—often described as “firm and putty-like,” capable of holding its shape without slumping. The mortar must be used within two hours of mixing, as the hydration process begins immediately.

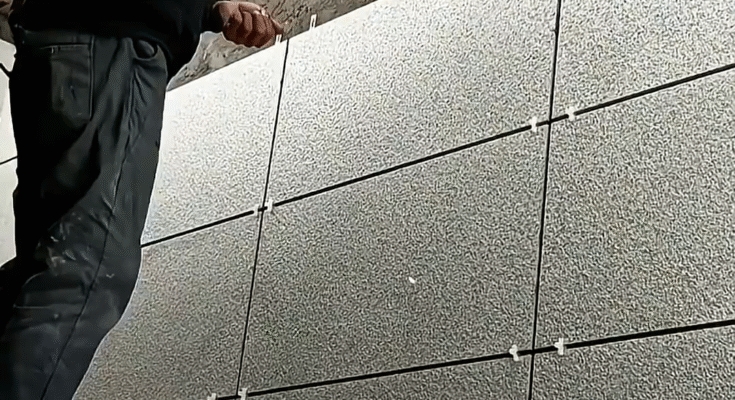

Phase IV: The Tuckpointing Process (Application and Tooling)

With the joints prepared and the mortar mixed, the application phase begins. This requires patience and a steady hand to ensure the joints are densely packed and properly finished.

Filling the Vertical Joints

The mortar is loaded onto a mortar board or hawk and applied using a small pointing trowel or a specialized joint filler gun. The vertical joints (head joints) are filled first. Mortar is firmly forced into the joint in thin, dense layers—typically two to three layers, rather than one thick application. This layering technique, known as buttering, ensures maximum compression and adhesion, eliminating air pockets. Each layer should be allowed to stiffen slightly before the next is applied.

Filling the Horizontal Joints

The horizontal joints (bed joints) are filled next, following the same layering principle. The mortar should be slightly proud (sticking out) of the wall face.

Tooling the Joint

The appearance and durability of the joint are determined by the tooling, which compresses the mortar and seals the surface against water. The joint is tooled when the mortar is “thumbprint hard”—it has lost its sheen but is still workable.

The most common and preferred finish is the concave joint, created with a rounded or S-shaped tooling iron. This finish sheds water effectively and compresses the mortar tightly. Other historical profiles include the V-joint, weather-struck joint, and flush joint. Uniformity in the tooling is essential for a professional and durable finish.

Phase V: Brick Replacement and Final Curing

In cases where bricks are cracked or severely spalled, they must be cut out and replaced entirely.

Replacing Individual Bricks

- Removal: The mortar surrounding the damaged brick is carefully removed using a hand chisel or a grinder with a masonry wheel. Extreme care is taken to avoid disturbing the adjacent bricks.

- Extraction: The center of the damaged brick is broken out using a hammer and chisel, and the pieces are pulled out. The remaining cavity is meticulously cleaned of all mortar fragments.

- Preparation: The cavity is wetted down, as with the repointing joints.

- Setting the New Brick: A replacement brick (which must match the original in size, texture, and color) is fully buttered on the top, bottom, and ends. It is then carefully slid into the cavity and tapped firmly into place, ensuring it is flush with the surrounding wall plane. Excess mortar is immediately struck off, and the remaining joints are tooled as per the repointing process.

Curing and Cleaning

Curing is the most overlooked yet most critical phase. Fresh mortar does not dry; it cures through hydration. This process requires slow, controlled evaporation of water. For the first two to three days, the repaired area must be kept consistently damp, usually by misting it lightly with water several times a day or by hanging damp burlap over the area. Protecting the area from direct sun, high winds, and rain for at least one week is crucial.

Once fully cured (typically 7 to 14 days before full strength is achieved), the final cleaning takes place. Any mortar smears or efflorescence that appeared during curing are removed. A stiff brush and water are the safest option. If a chemical cleaner is necessary, a dilute solution of muriatic acid may be used, but only with extreme caution, proper neutralisation, and prior testing on a small, inconspicuous area to avoid etching or permanently staining the brick face.

In summary, the process of fixing wall bricks is a commitment to material science, detailed craftsmanship, and historical preservation. By following the meticulous steps of proper inspection, deep raking, material matching, high-compression application, and controlled curing, a brick wall can be restored to its original strength and beauty, securing the structure for decades to come.