The deformation of solid metallic stock, specifically metal rods, is a foundational process in modern manufacturing. Known collectively as plastic deformation, bending is the controlled permanent shape change of a material without fracturing or failure. The ability to precisely shape rods—whether solid, round, or square—is critical for structural integrity, aesthetic design, and functional performance across sectors including automotive, furniture, piping, and specialized machinery.

This report comprehensively examines the underlying metallurgical principles, the mechanical methodologies, and the critical factors that govern the successful and accurate bending of metal rods.

I. Fundamentals of Plastic Deformation

Successful metal bending relies on controlling the material’s response to applied stress. The key concepts are the material’s stress-strain behavior and the geometry of the deformation.

The Stress-Strain Relationship

When an external force (stress) is applied to a metal rod, it experiences an internal deformation (strain). This relationship is graphically represented by the stress-strain curve.

Initially, the metal undergoes elastic deformation, where the rod returns to its original shape once the stress is removed. This phase ends at the Yield Strength ($\sigma_y$). For bending to be permanent, the applied stress must exceed the yield strength, pushing the material into the plastic deformation region. In this region, atomic bonds are permanently rearranged, and the shape change is irreversible.

The material must also possess sufficient ductility—the ability to deform plastically without fracturing—to withstand the bending process. The maximum stress a material can endure before necking or failure is the Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS).

The Neutral Axis and Stress Gradient

During bending, not all material within the rod experiences the same strain. The inner radius of the bend experiences compressive stress and strain, causing the material to thicken slightly. Conversely, the outer radius of the bend experiences tensile stress and strain, causing the material to thin and lengthen.

Between these two zones of compression and tension lies the Neutral Axis. This is an imaginary plane or line within the cross-section where the material experiences zero longitudinal stress and strain. For an ideal bending operation, the neutral axis remains precisely at the geometric center of the rod’s cross-section. Precise bending calculations rely heavily on knowing the location of this axis to accurately determine the required bend allowance.

The Challenge of Springback

A phenomenon inherent to all cold bending processes is springback. When the external bending force is released, the rod’s elastic energy stored during the deformation is partially recovered, causing the bend angle to partially relax, or “spring back,” to a slightly shallower angle than the bend tool’s angle.

Springback is directly proportional to the material’s yield strength and the bend radius. Higher yield strength materials (like hardened steels) and larger bend radii result in greater springback. To counteract this, manufacturers use techniques such as overbending (bending past the target angle) or coining (applying high compressive pressure at the end of the stroke to force the bend set). Accurate springback compensation is vital for achieving precise geometric tolerances.

II. Primary Methodologies for Rod Bending

The choice of bending method for metal rods depends heavily on the rod’s diameter, the material, the required bend radius, and the volume of production. The most common techniques fall under three categories: press bending, rotary bending, and roll bending.

A. Press Brake Bending (Die Bending)

While primarily associated with sheet metal, press bending is also used for simple, large-radius bends in solid rods, particularly for low-volume or prototyping work. The rod is placed over a V-shaped or U-shaped die, and a punch forces the rod down into the die cavity.

- Air Bending: The rod only contacts the die at two points and the punch tip at one point. The final bend angle is achieved by controlling the punch stroke depth, relying on the material’s specific springback characteristics. This method offers high flexibility as multiple angles can be formed with the same set of tools.

- Bottoming: The rod is forced completely to the bottom of the V-die, minimizing springback through direct compression. This method offers greater angular precision but requires specific tooling for each desired angle.

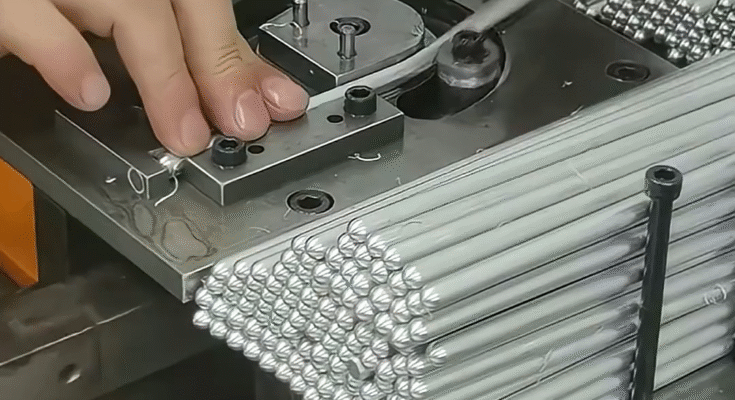

B. Rotary Draw Bending

Rotary draw bending is the most precise and common method for bending rods and tubes, especially when tight radii or complex, three-dimensional bends are required, such as in railings or automotive chassis components.

The process uses specialized tooling mounted on a rotary bending machine:

- Clamp Die: Grips the rod end to prevent slippage.

- Bend Die (or Radius Die): Rotates to pull the rod around the required radius.

- Pressure Die: Holds the rod against the bend die during rotation.

- Mandrel (for Tubes): While rods generally don’t require an internal mandrel, for thin-walled tubes (often used in rod-like applications), a mandrel is inserted to support the inner wall and prevent wrinkling and collapse (ovality).

This technique ensures that the rod’s cross-section remains highly consistent throughout the bend, crucial for maintaining structural integrity and predictable load-bearing capacity.

C. Roll Bending (Three-Roll Bending)

Roll bending is used to create large-radius curves, arcs, and complete rings or helical coils. It involves passing the rod through a machine with three rollers arranged in a pyramidal or triangular configuration.

- Mechanism: The two bottom rollers are fixed, and the top roller (the forming roller) is adjustable. By gradually lowering the top roller, the rod is continuously deformed as it passes through the rolls, creating a large, smooth curve.

- Applications: This is ideal for manufacturing components like large diameter hoops, pipe supports, and reinforcement cages, where the required bend radius far exceeds the limitations of press or rotary dies. The precision of the final curvature is achieved through multiple passes and incremental adjustments to the top roller’s position.

III. Critical Factors Influencing the Bending Outcome

Several mechanical and metallurgical parameters must be carefully managed to ensure the bent rod meets performance and tolerance specifications.

Material Properties and Temper

The material’s specific alloy composition and temper (hardness) are the most significant factors. Ductile materials like low-carbon steels, aluminum alloys, and coppers are easily bent with less risk of cracking. High-strength steels and hardened alloys have higher yield strengths, which requires significantly more bending force and, critically, results in much greater springback. The bending equipment must be powerful enough and robust enough to handle the increased tonnage and the required overbending.

Minimum Bend Radius

Every material has a Minimum Bend Radius ($R_{min}$), which is the tightest bend possible without causing surface cracking on the outer tensile face of the rod. $R_{min}$ is usually defined as a multiple of the rod’s diameter ($D$). Bending below $R_{min}$ induces excessive tensile strain, leading to localized necking and catastrophic failure.

$$R_{min} = C \times D$$

Where $C$ is a factor dependent on the material’s ductility and thickness-to-diameter ratio.

Cold Bending vs. Hot Bending

Most bending of metal rods is performed at room temperature (cold bending). This process is energy-efficient, maintains high surface quality, and results in a phenomenon known as strain hardening (or work hardening), which increases the strength of the rod at the bend location.

However, for very thick rods, materials with low room-temperature ductility (e.g., certain refractory metals or highly tempered alloys), or when extremely tight radii are needed, hot bending is employed. The rod is heated above its recrystallization temperature before deformation. Heating drastically reduces the material’s yield strength and increases ductility, allowing for significantly greater deformation with less force and virtually eliminating springback. The trade-off is higher production cost, lower dimensional accuracy, and potential surface oxidation (scaling).

Tooling Condition and Lubrication

The quality and maintenance of the bending tools directly affect the final product quality. Tools must be made of materials harder than the rod (e.g., hardened tool steels) to prevent premature wear. Furthermore, applying the correct lubricant is essential in rotary draw bending. Lubrication minimizes friction between the rod and the dies, preventing scoring, reducing wear on the tooling, and ensuring smooth material flow during the deformation, which helps mitigate cracking and wrinkling.

IV. Quality Control and Process Optimization

The manufacturing process must incorporate checks and compensation methods to guarantee dimensional accuracy.

Addressing Cracking and Wrinkling

- Cracking occurs on the outer radius due to excessive tensile stress. This is remedied by ensuring the bend radius is above the material’s $R_{min}$ or by switching to hot bending.

- Wrinkling occurs on the inner (compressive) radius, often when the rod is thin-walled or bending with a very tight radius. For rods, this is less common than for tubes, but when it does occur, it indicates insufficient material confinement. This can be mitigated by ensuring proper pressure die force or by reducing the bend speed.

Predictive Modeling and Simulation

Modern bending operations rely on predictive modeling (Finite Element Analysis or FEA) to simulate the bending process. This allows engineers to accurately calculate the required overbend angle to compensate for springback, determine the precise tonnage needed, and predict potential failure points (cracks or wrinkles) before any physical material is consumed. This reduces setup time, minimizes material waste, and is key to achieving “first-part-right” production goals, especially with expensive or exotic alloys.

Conclusion

The bending process of metal rods is a sophisticated interplay of material science, mechanical engineering, and precision tooling. By understanding the fundamentals of plastic deformation, particularly the role of the neutral axis and the calculation of springback, engineers can select the appropriate methodology—whether press, rotary draw, or roll bending—to meet stringent application demands. The continuous refinement of process parameters, informed by material properties, bend radius constraints, and modern simulation techniques, ensures the production of high-quality components essential for the structural integrity and reliability of manufactured goods worldwide.

This process is continually advancing with the integration of automation and intelligent compensation systems that adapt to material variability in real-time, promising even greater precision and efficiency in the future of metal forming.